TWO ATTENDANTS at St Audry's Hospital whose military and civilian careers were intertwined - both were serving on the HMHS Britannic on her final voyage to Mudros to pick up wounded soldiers from the Salonika Campaign. This is their story:

Edward Knight Jordan was born on 28th February 1877 in Walworth, London. His parents, both from Suffolk originally, were called Harry and Harriet (née Knight): Harry came from Wickham Market and Harriet hailed from three and a half miles down the road, in Marlesford. The family returned to Suffolk sometime before Edward’s father died in 1888, when Edward was eleven. In 1891, a fourteen-year-old Edward was working as an errand boy and lived with his brothers and mother on Cumberland Street in Woodbridge.

Frederick John Dunnett, the man with whom Edward’s life would be strangely interwoven, was born on 17th July 1894 in Hasketon, Suffolk; his parents were Frederick and Eliza. Edward, was seventeen years his senior.

Seven years later, Edward and his family had moved to Seckford Street in Woodbridge and Edward had a job as a barman; his mother worked as caretaker for the Seckford Reading Room.

In 1911, Frederick and Edward were living two miles away from one another: Edward still on Seckford Street and Frederick at Foxborough Farm Cottages in Melton, where his father was employed as the farm bailiff. Frederick Jr. was a horseman. Edward was employed by William Woodruffe as a painter.

Cap Badge of the Royal Army Medical Corps

It was in this year, 1911, that Frederick joined Edward in the Territorial Army. Seventeen years Frederick’s senior, Edward had enlisted in the 1st Suffolk Volunteer Brigade back in 1904, followed by the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) in 1909. Frederick became part of the 1st (Territorial) East Anglian Field Ambulance on 4th January 1911.

Both men would have met when members of the 1st East Anglian Field Ambulance where they had signed the “Imperial Service” pledge. The pledge meant that they could wear a silver “Imperial Service” badge on their uniform and, if the need arose, they would be expected to serve overseas. A year later, in Liverpool, the ill-fated RMS Titanic embarked on her maiden voyage on the 10th April 1912. On the 15th, it sank beneath the waves. Of the estimated two thousand two hundred and twenty-four passengers onboard, more than fifteen hundred died when the ship’s starboard side struck an iceberg. The blow caused the hull’s seams to buckle and separate, allowing water to begin to seep in. Two hours after the initial collision, the RMS Titanic had sunk below the waves, the second-largest passenger vessel to lie on the sea floor.

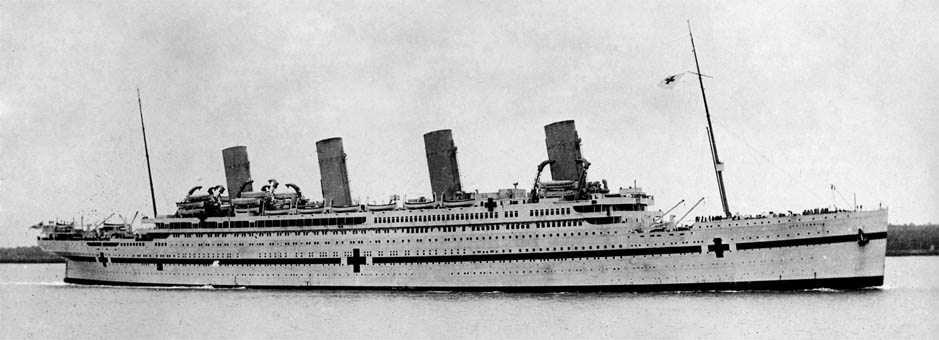

On 26th February 1914, the sister ship to the RMS Titanic and RMS Olympic and third vessel of the White Star Line’s Olympic-class of ocean liners, the HMHS Britannic, was launched from the Harland and Wolff yard in Belfast. Both the Britannic and the Olympic were requisitioned by the British Government during the First World War; the Olympic was converted into a troop carrier whereas the Britannic was eventually fitted out as a hospital ship to evacuate the sick and wounded from the Gallipoli Campaign. The Britannic’s maiden voyage began on 23rd December 1914 with a ships' crew of six hundred and seventy-five and a medical team consisting of one hundred and one nurses, fifty-two officers and three hundred and thirty-six other ranks. In comparison, the RMS Titanic had an estimated crew of eight hundred and eighty-five members, of which deck hands accounted for sixty-six, engine for three hundred and twenty-five and victualling, four hundred and ninety-four.

As a hospital ship, the Britannic made three voyages: two ferrying casualties back to England from Gallipoli and a third anchored off Cowes on the Isle of Wight, over the course of a month, where she was used as a floating hospital for the casualties of the Western Front. When the Gallipoli Campaign ended, there was no longer a need for a hospital ship the size of the Britannic and the government handed her back to her owners.

Upon her return to Harland and Wolff’s yard in Belfast, the Britannic was laid up, awaiting refitting back to a passenger liner, when the government recalled her into service again. On 24th September 1915, she made her fourth journey to the Greek island of Mudros which was being used as a staging post to treat those wounded from fighting in Egypt, Palestine and Salonica — on board were two men from Melton.

At the outbreak of war, Edward and Frederick, alongside Robert Pyke – another Melton man – were called up. Frederick was twenty years old; Edward was thirty-seven. On 24th August, all three were en route to France with the 11th Field Ambulance, where they spent their first six months involved in The Battle of the Marne, The Battle of the Aisne and The Battle of Messines. They were parted in June 1915 however, when Frederick contracted scarlet fever and was returned to England for treatment.

Once recovered, Frederick spent the last months of his service period at St David’s Hospital on the island of Malta with 30 Company RAMC. In late December 1915, he boarded the SS Soudan, bound for England and his discharge on 8th January 1916. Edward, in the meantime, remained with the 11th Field Ambulance, seeing action at the Second Battle of Ypres between 22nd April and 25th May. At the end of his service period in March 1916, Edward returned to England.

Frederick and Edward found themselves in one another’s company again when they became attendants at St Audry’s Hospital – however their time on staff was to be brief. Due to the number of war casualties, particularly from the Battle of the Somme, more men were needed. The Military Service Act of 1916 was amended so that time-expired soldiers like Frederick and Edward could be called up to serve again. And so, not even six month’s after their discharge, Frederick and Edward’s employment records state they were “called to colours” and they left to re-join the RAMC, this time aboard the HMHS Britannic, on 5th July.

The HMHS Britannic struck a mine and sank within forty minutes on 21st November 1916.

The HMHS Britannic left Southampton for Mudros on 24th September, stopping for coal in Naples a week later. On the 3rd October, she arrived at Mudros. A huge number of casualties were transported home to Southampton on both this trip and the one following, a carbon copy of its predecessor, departing Southampton on 20th October and returning on 6th November.

In the brief period between the Britannic’s second and third voyage, Edward travelled to Newcastle-upon- Tyne to marry Elizabeth Fitzpatrick. Two days later, he and Frederick were on board the Britannic for the last time.

At 14:23 on 12th November 1916, the Britannic left Southampton for the same voyage to Mudros with the aim to collect more casualties and return them home. She passed Gibraltar in the early hours of the 15th, reaching Naples on the 17th for their usual coaling stop. Poor weather kept the Britannic docked until Captain Bartlett decided to take advantage of a brief lull and they left Naples during the afternoon of Sunday 19th November. By the following morning, the storm had died down and two days later, the Britannic passed Cape Matapan.

At 08:21 on the morning of the 21st November, the Britannic was sailing at full speed through the Kea Channel between Cape Sounion and Kea Island when an explosion rocked the ship. It was not apparent at the time what the cause was, but it was later discovered to have been a mine.

Just like the North Atlantic iceberg to its sister ship, the mine’s blast had torn a hole in the Britannic’s starboard side. Damage to the ship’s bulkheads allowed water to fill four of the watertight compartments (one less that Titanic) and, in order to try and salvage the ship, Captain Bartlett attempted to beach the ship on Kea Island, just off the coast of mainland Greece. By this time the ship was listing to starboard and water poured in through portholes left open by the medical staff to ventilate the wards.

The scale of these gigantic ships may be judged by the man standing near the base of

the rudder. This is the building of the sister ship to HMS Britannic – HMS Olympic.

Unbeknown to the captain, some of the crew launched two lifeboats without waiting for permission. One of those boats was drawn into the propellers, resulting in thirty people losing their lives; the captain, unaware that the lifeboat had been launched, hadn’t stopped the engines.

By 09:00, nearly forty minutes after the initial hull breach, water had reached the upper decks. Captain Bartlett, realising there was no hope of reaching Kea Island, stopped the engines and ordered the crew to abandon ship. Seven minutes later, the Britannic had disappeared beneath the waves to become the largest ship lost during the war and remaining the biggest passenger vessel on the sea floor — stealing the crown from its sister ship, the RMS Titanic.

Of the one thousand and sixty-five people on board, the thirty men on the lifeboat were the only ones to lose their lives. Both Edward and Frederick were among the rescued and were taken to Malta where, according to their medical records, they were treated for “nervous shock”. They were then shipped to France, where they travelled via cross-country train to Boulogne, arriving back in England late December 1916.

On 9th June 1917, Frederick and Edward were separated again when Edward was posted to join the 60th General Hospital in Salonika; he remained here for the rest of the war. Frederick, on the other hand, was sent to the front line, arriving in Le Havre on the 18th May 1917. He was then sent on to a depot camp in Rouen, the location of several military hospitals. From here, Frederick was posted to join the 35th Field Ambulance who were attached to the 11th (Northern) Division, in the Ypres area. Frederick remained with the 35th Field Ambulance until the end of the war; he would have been involved in the Battle of Messines, The Battle of the Langemarck, The Battle of Polygon Wood, The Battle of Broodseinde and The Battle of Poelcapelle. In 1918, the 35th Field Ambulance moved south and were at Arras for The Battle of the Scarpe in 1918 and The Battle of the Drocourt- Quant Line. They also fought in The Battles of the Hindenburg Line and The Battle of the Sambre.

Frederick and Edward were demobilised in March 1918 and, the following month, were reunited when they returned to their positions as attendants at St Audry’s Hospital.

Edward’s wife, Elizabeth, was still living in Newcastle at this time and she moved down to live with him at Hillside on Melton Hill. In 1939, aged sixty-two, Edward was working as a park attendant in Woodbridge having stopped working at St Audry’s a few years earlier. At this time, he and Elizabeth had moved to Seckford Street, to the same street Edward had spent his adolescence, to care for his now-bedridden mother, Harriett.

Frederick married Maud Last in 1926 and they had one child, a daughter, Daphne. In 1939, the family lived at Sunnyside, Pettistree, and he was still an attendant at St Audry’s; he was forty-five.

For their war service, both Edward and Frederick received the 1914 Star with Clasp and Rose, and the British War and Victory Medals. It is unknown whether or not Frederick and Edward were friends. The RMS Titanic and the HMHS Britannic remain on the ocean floor.